Forensic Recipes

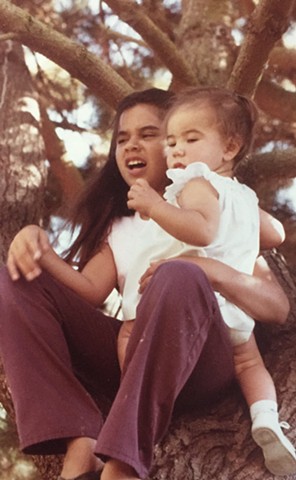

When I was a child, both of my older sisters hid me to keep me away from the violence of my parents. Leah, who I have always known, would grab my infant body and take me to the only place in reach where my parents never fought: up into the limbs of a tree. Jacqueline, who I met later, could anticipate the crash of flying objects, shuttering me and our little brother to the furthest room of the house and into the closet if necessary, where the curses were muffled. She would quickly pour out legos, snatch favorite toys, so we wouldn’t grow restless and throw a fit at being so suddenly contained. We babies threw fits anyways and there was no escaping loud hell for poor Jacqueline.

How did Leah and Jacqueline know to do this? Who told them to love me, to protect me? Didn’t I steal from their portion of our parents? Maybe they were grateful for that. Maybe the exclusive attention of our parents wasn’t the promise of undivided love it should have been. Yes, my sisters loved me without knowing why, though they knew how. How they knew how is a mystery and miracle I return to time and time again when I feel the tightness or spill of my own heart.

It comes from pigs and cows. The last of their value boiled right out of their bones. I guess it is then dried and crushed to a powder portioned out into paper packets. I used to date boys with mohawks, “Knox!” they’d say when I asked for their beauty secret. Bones in the hair, bones in the bowl, loud overstated colors covering up for the bones. You add the sugar and water later, but the bones give bounce and life. It has give because of the bones.

The sugar comes in many pound sacks—best to fill your arms with them and buy all at once at the cash register offering no explanation, just a down payment on diabetes 2. Who knows what hell the sugar comes from now. I’m sure someone still has to die. I can imagine the slaughterhouse line for the pigs and cows, the rendering vats, but sugar is that ingredient so common it’s means of production might as well be invisible, and surely, once explained will seem too strange, too impossible to remember as a fact like the erotic truth of a cashew fruit or the tomb of a fig wasp. Sugar was a plantation crop in the West Indies. Lots of rebellion and fire and sticky residue on the charred earth.

There’s a dash of citric acid, and if you can’t recall that taste think back to the 5th grade when we were all standing in a circle sucking intently on warheads to see who would break first from the bright sour chemical searing our dumb, young tongues. You only use a little of the acid in this recipe though, to break up the sugar and bone. To preserve it.

And then gallons of water, first to boil ‘til the crystals in all the powders loosen and within the proper tolerance reform as totally different structures, absorbing the moisture, quenching the protein bonds so they stay supple and wet. No point in saying where the water comes from; it comes from me, it comes from you, we pass it back and forth. The syrup cools, reorganizing into a slow solid. You can heat it up, return it to a liquid, cool it down, solidifying, then all over again until the gas in your stove runs out. It won’t ever refuse the transformation back and forth if the conditions are right. That’s part of why I love it—its transmutability, even at the end of the end of its line.